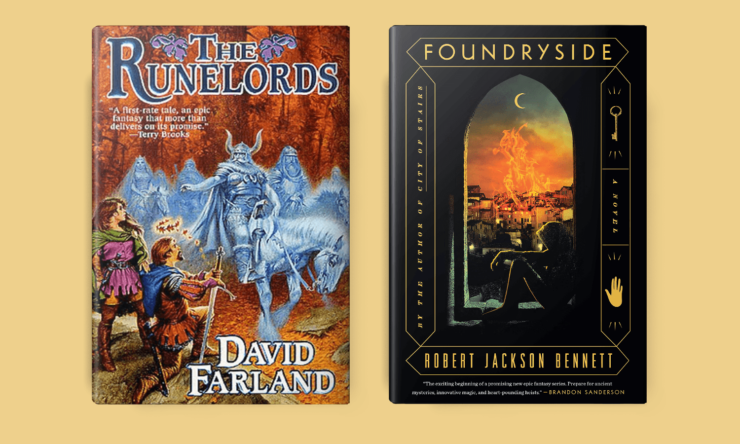

Robert Jackson Bennett’s Foundryside made its way into the world in 2018 and quickly found an audience as one of the most creative and fun new fantasies around. Building on his success with The Divine Cities trilogy, Bennett found a groove with a world built around magitech and politics.

Meanwhile, David Farland’s The Runelords has been collecting fans since the late ’90s, with multiple titles in the series—of which eight books have been published so far—hitting the The New York Times Best Seller list. Split into two sub-series (The Earth King series and the Scions of the Earth series), The Runelords truly is an epic fantasy, in terms of scope, featuring over a dozen major POV characters and spanning multiple worlds, and multiple magic systems.

Despite being conceived decades apart and having rather disparate settings, The Runelords and Foundryside share common ground in their exploration of economics through magic. While many fantasy authors have tackled economic theory and practice in their stories, weaving the complexities of trade, finance, and cultural stability into the fabric of their worlds—consider the work of Daniel Abraham, Patrick Rothfuss, Elizabeth Bear, Max Gladstone, and Ann McCaffrey, to cite a few examples—it’s rarer to find fantasy novels in which the magic system itself is inextricable from matters of wealth and economic injustice, and the morality underlying both. Farland and Bennett, for all their differences, have both created worlds in which magic is inseparable from its economic impact, and its costs on both financial and human levels play central roles in the unfolding of their stories.

In The Runelords, the first of two magic systems we encounter in the series is a relatively straightforward elemental magic. Earth Wardens, flameweavers, water wizards, and Sky Lords manipulate the four classical elements, with arcane politics underpinning the wizardry. But the second magic system is much more inventive, and gives Farland a brilliant opportunity to expand his fantasy world. Built around runes and a magic material called blood metal, Farland gives us a system of endowments between Runelords and Dedicates, wherein physical and mental attributes can be transferred from one person (the Dedicate) to another (the Runelord). In an instance where, for example, a Dedicate is giving an endowment of sight, she will be left blind; the Runelord will be able to see twice as well. But there’s a catch—if the Dedicate dies, the Runelord loses the endowment.

The result is superhumanly powerful warriors: Runelords imbued with the strength, stamina, speed, and senses of many people. Since Runelords are so difficult to engage in actual war, the action shifts to a new battlefield: assassins are routinely sent after the weakened and often defenseless Dedicates. To counter this strategy, Runelords begin building huge Dedicates’ Keeps and guarding them with other Runelords, and the game of chess continues…

This system of endowments has far-ranging effects on Farland’s world. He doesn’t limit his exploration of the magic to the battlefield, instead chronicling how it has become an inextricable part of society. Lord and ladies commonly purchase endowments from the poor (a practice frowned upon by some, though not many). In the opening pages of The Sum of All Men, the first book in the series, we meet a young lady whose poverty-stricken mother and sisters saved for years to give her endowments of wit and glamour, so that she might catch the eye of a bachelor merchant or lord. The esoteric scholars known as the Days espouse a secret philosophy that, when examined a certain way, views the taking of endowments as a nearly ultimate evil. Some outlaws and desperate lords stoop to taking endowments from dogs, and are hanged and denounced as “Wolf Lords” for their ethically dubious practices.

Taking his magic system to such intricate lengths allows for a richer story, and Farland doesn’t shy from plumbing the depths of these concepts. One of his protagonists wrestles with the morality of taking endowments from others, even when willingly given—though such endowments appear to be his only hope of salvation. Another has her glamour (and self-confidence) stripped from her when an invading lord blackmails her into giving an endowment. Her story, moving from near-suicidal depression to acceptance of who she is, drives home the deeper implications of the Dedicates’ lives.

With artisans, soldiers, and workers given the benefit of endowments, industry and wealth in The Runelords are concentrated around who has the most blood metal, the best facilitators (the men and women who perform the ritual that transfers endowments through the branding of runes), the most Dedicates—and whose keeps are the best-defended.

In Foundryside, on the other hand, magic interacts with the economy in very different ways; in fact, it’s inextricably tied to every level of society. In Bennett’s world, arcane runes called scrivings can be used to “convince” objects to act in ways against their nature. Wooden supports for buildings are made to believe they’re metal, crossbow bolts can act like they’ve been dropped from 40,000 feet, and doors are convinced they can’t be opened.

The main setting, the city of Tevanne, is dominated by “campos,” compounds run by extraordinarily rich families who have a monopoly on scriving. Some underground scrivers maintain a living, but at great personal risk. The unchecked ambition of the society has evolved into pure avarice, with the campos even going so far as to invest in scriving experiments on plantation slaves. It’s easy to interpret this setting as a direct critique of late-stage capitalism—and there are certainly elements of that at play here—but fundamentally, it simply looks at the moral decay of a completely unbalanced economic system, whether that’s achieved through capitalism or any other system that benefits the privileged few at the expense of the many.

In Tevanne, the situation has devolved into a sort of economic oligarchy, rife with nepotism and cronyism, with a nice base of anarchy to round things out. The novel’s protagonists provide excellent views into different aspects of this inequality: Sancia is a thief and former slave, living hand to mouth and barely surviving; Gregor, the only remaining son of one of the city’s wealthiest families, has cast aside much of his mercantile privilege in an attempt to establish a constabulary and bring order to the anarchy. As the story progresses, the inner workings of the campos are revealed and even greater injustices are explored. The presence of slavery does not fade into the background, and is in fact brought to light move fully in other, more sinister manifestations than the overt plantation-style slavery set out at the start.

And, of course, built into all this is scriving. On the surface simply a rune-based magic, it’s also easy to view scriving as a kind of programming, with AIs helping to run the city and a technological AI arms race in full force among the rival campos and families. Bennett clearly enjoys delving into the details of the system he’s created, digging deep into how scrivings work, and the resulting descriptions provide a fascinating reflection of how actual programming works in our own world…

Bennett’s Founders trilogy, of which Foundryside is the first volume and the newly published Shorefall is the second, is very much a contemporary look into issues of inequality, mercantilism, and yes, capitalism—all through the lens of an exciting heist fantasy, perfect for fans of The Lies of Locke Lamora and Mistborn. Meanwhile, Farland continues work on the long-awaited ninth and final installment in The Runelords, tentatively titled A Tale of Tales.

Depending on your taste in fantasy, you might be more familiar with Farland’s enduring series, or you may have discovered Bennett’s work more recently. In the end, however, both authors have created worlds that never shy away from exploring thought-provoking moral and ethical questions through a magical—and magically economical—lens. There are fascinating depths to explore in either (or both) of these fictional universes, especially for those who interests lie in the realm of economics.

Drew McCaffrey lives in Fort Collins, CO, where he’s spoiled by all the amazing craft beer. He co-hosts the Inking Out Loud podcast, covering science fiction and fantasy books (and some of that Colorado craft beer). You can find him on Twitter, talking about books and writing, but mostly just getting worked up about the New York Rangers.